In which Emily quotes Joan Didion, gets excited about Ada Lovelace, and is really pleased that she’s no longer in the Bismarckian morass of high school politics.

Footnotes are glorious things.

They’re elegantly spun sugar on the top of a fancy caramel-and-chocolate Dobos Torte. They’re perfectly blocked lacework on the edge of a beautifully hand-knit shawl. They’re gorgeously ornamental finishing touches to a lovingly crafted work of art.

They’re also the steady basso continuo of a Baroque aria. They’re the geometric precision of a Velazquez painting. They’re technical prowess and the nearly invisible foundation beneath glitteringly virtuosic performance.

In his excellent The Footnote: A Curious History, Anthony Grafton talks about becoming fascinated with footnotes and the way that they convey authority and expertise in modern academic writing. They are the solid foundation that shows careful thought and that lets you advance your wild new idea about Alice in Wonderland, or Hamlet, or nineteenth-century Prussia, or whatever it is that you have a lot of thoughts about. But footnotes are also deliciously ornamental pieces of whimsy and silliness, where serious scholars let their hair down a bit and indulge in playfulness or only semi-responsible speculation. And they’re places of literary play where GREAT modern writers like David Foster Wallace, Jorge Luis Borges, Susanna Clarke, Vladimir Nabokov, and Mark Z. Danielewski — as well as much earlier AWESOMELY WEIRD writers such as Edmund Spenser, Laurence Sterne, and Alexander Pope — mess with tone, realism, world-building, literary criticism, and the very nature of narrative writing in the first place.

(Of course, every occasionally over-committed grad student also will appreciate the way that footnotes can make it easier to hit a required minimum page count on a paper while indulging in digressions and straying a bit from one’s intended argument.)

Footnotes give authority, power, and foundation but also allow for the display of skill, artistry, and playfulness. They allow for digressions and speculation and personality. At their core, footnotes are digressive even as they represent an author’s act of winnowing. In this, they ask us to think about how we tell stories.

There’s a reason that we narrativize stuff. Our brains really like consuming events in linear, causal patterns. It’s like learning, for example, that WWI happened because of Bismarck and the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. That’s a horribly simplistic summary, but it’s not wrong. And it’s simplified so that it can be easily consumed and internalized by generations of high school students who are kind of distracted by their own Bismarckian alliances about who sits next to whom and who likes/hates/has-a-crush-on whom. We winnow facts into narratives in order to make sense of our histories and our identities and indeed our world.

We do this sort of narrativizing all the time. Joan Didion has a great line at the opening of her essay “The White Album” about how “We tell ourselves stories in order to live.” Her point is about how we narrativize our own lives — as well as tell fictional stories. But seriously. We’re constantly telling stories about our histories, our lives, and our world, and in doing so, we’re constantly sidelining certain issues and ideas. We turn them into footnotes.

But when we tell those histories, those footnotes are still important. They’re where that historian proves that she’s got her facts right, where she builds credibility and authority, and where she hints that the situation is more complicated than she just made it out to be. Maybe she’s more irreverent in her footnotes, maybe she throws a little shade — or maybe she just gives you additional pieces of information to remind you that the world is more complicated that she just made it out to be. And that’s why I love footnotes: they do all sorts of weird and fascinating things with authority and with storytelling.

Fundamentally, footnotes allow historical narratives to stand (providing authority and citations) while also “well-actually”-ing the entire narrative project, reminding us constantly that the world mostly makes sense but that it is also infinitely complex and very very weird. They let us tell stories, but they also make us think about what it means to tell a story. They make us think about how we find Truth in stories and about what parts of the stories we choose to leave out.

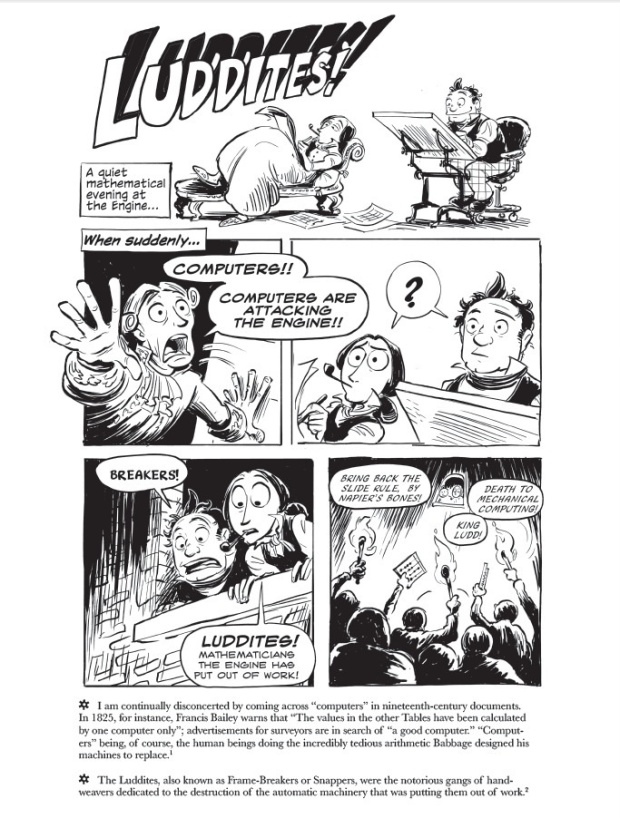

In her stunningly clever The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage (which I briefly got excited about months ago but only recently got around to finishing), Sydney Padua does AMAZING things with her footnotes.

First off, because she’s working in a comics medium and is playing with the conventions of the eighteenth- and nineteenth-century book market, Padua seems to be super aware of the placement of the footnote on the page. Using both footnotes and endnotes, she creates densely complicated stories which force you as the reader to be aware of the experience of reading in a way that you wouldn’t necessarily be otherwise.

What do you read first? Do you read all of the comics then the footnotes? Should you flip between the story and the endnotes or just read the whole story at once and then read all of the endnotes? Should you read the footnotes first? Will they spoil the comics? Padua makes her reader become self-consciously aware of how she’s constructing a story when she repeatedly interrupts whimsical alternate universe steampunky story with her footnotes and endnotes.

Then inside those footnotes, Padua complicates her story by including digressions, she provides citations of primary historical documents, and she clarifies when her fictionalized versions of Charles Babbage, Ada Lovelace, George Eliot, and the entire nineteenth-century crew do something slightly anachronistic or ahistorical. Giving FASCINATING details about the weird lives of Victorians, Padua’s doing what footnotes do, and doing it excellently.

But the last section of her book BLEW me AWAY. Ada Lovelace kind of is a footnote to history, in a lot of ways. She’s the wildly non-literary daughter of Lord Byron who arguably theorized computer programming decades before the first computer. The Ada Lovelace of popular imagination, Padua notes, “was a supergenius mathematical prodigy and co-inventor of the computer.” At the same time, though, some Babbage scholars grumble that Ada Lovelace didn’t actually do any proto-computer-programming but rather has just become a cipher for the dreams of steampunk-loving feminists. In the last section of The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage, the character of Ada Lovelace falls, Alice-in-Wonderland-like, into an alternate dimension. In this weird, metaphorized world, Lovelace finds herself literally followed around by a giant asterisk — because, as the footnote reminds us, “Anyone who has read more than a little about Ada Lovelace will become gradually aware of an asterisk that hovers over her status as ‘the first computer programmer.’” The point of this increasingly menacing asterisk, though, isn’t to explode our dreams about an awesome STEM-loving Victorian lady. Instead, as Lovelace finds herself first marginalized and then swelled up by the drawings themselves, Padua plays with the stickiness of narratives of history and the impossibility of ascertaining Historical Truth, even in the context of the eponymous mathematically inclined heroes of the book. Her footnote observes:

“Both of these competing cartoon Avas, Super-Lovelace and Nega-Lovelace, are constructed from the ambiguous jumble of letters, papers, contemporary descriptions, etc., etc., which are the far from mathematically precise stuff of history. A footnote hardly knows what to think!”

Padua doesn’t resolve the true nature of the historical partnership between Ada Lovelace and Charles Babbage, and she doesn’t firmly delineate which parts of computer programming owe their existence to Ada Lovelace. But in this final section, she draws upon Alice in Wonderland, abstract mathematics, and the materiality of the printed book in order to reflect upon the way that we narrativize and construct history — and the authority that we give to these narratives.

We’ll never know exactly what Ada Lovelace contributed to history. But that’s okay. Because, as footnotes remind us, the world is simultaneously cooler and weirder than we imagine.

In The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage, Sydney Padua plays with the ornamentation, the self-reflexivity, the authority, the digressiveness, and the playfulness of footnotes. And I loved it. If you’ve made it this far through a post on why footnotes are cool, you owe it to yourself to check out her book.

Happy Reading (and Footnoting)!